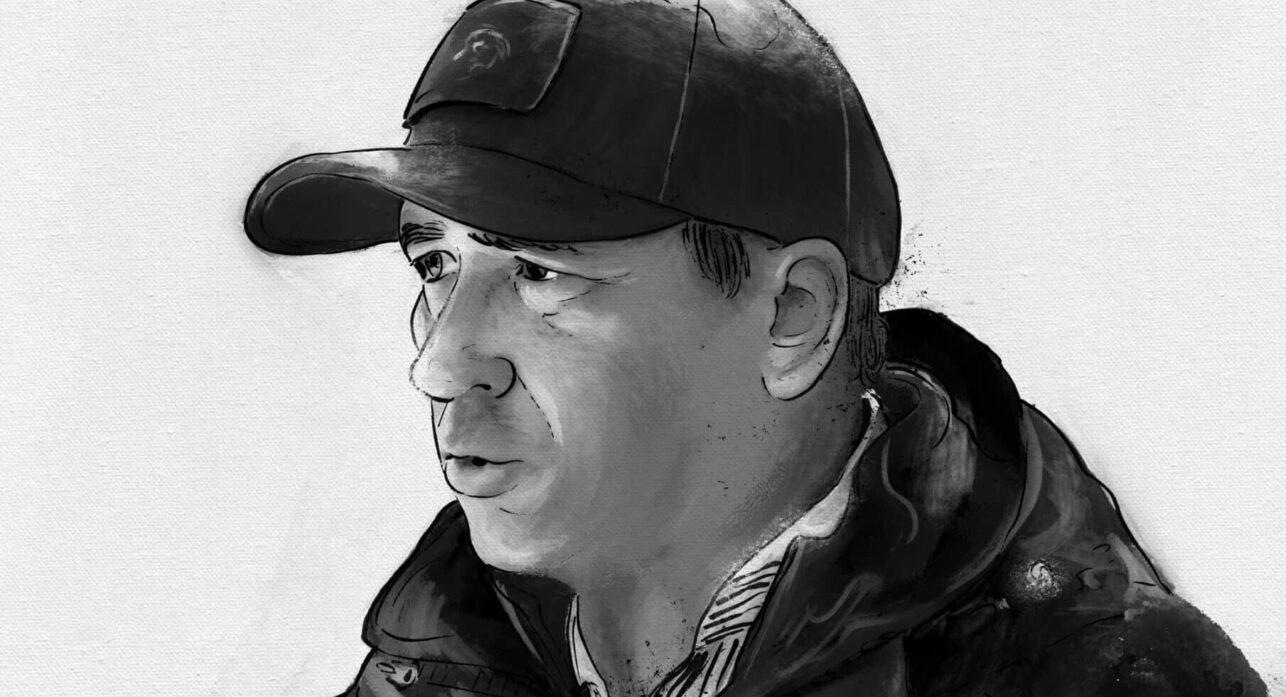

Talking with Vasilis Pateras leaves you with the feeling that you are speaking to a man who has lived a great deal, yet insists on standing low, almost at the waterline.

by Labis Tagmatarhis

President of the Hellenic Frogmen Association, winner of one of the most demanding races imaginable – the circumnavigation of Great Britain by powerboat – shipowner, quiet benefactor, founder of Axion Hellas, honoured by the President of the Hellenic Republic – and yet, when you ask him how he would like to be remembered, he always returns to the same word: “sailor.”

Perhaps because, for him, being an “always sailor” is neither a profession nor a title. It is a way of seeing the world: knowing that every harbour is temporary, that every fair weather can change, that every journey has meaning only if you do not make it alone.

And as long as there are remote border islands waiting for a boat with doctors, naval outposts that need support, young people seeking examples rather than words, it seems that Vasilis Pateras will continue, in his own way, to justify the title of his book: Always a Sailor.

Born into a family of shipowners – fourth generation – raised among wooden bunks, the smells of tar and diesel, salt that never quite washes off, he learned from childhood that life is measured in nautical miles, not kilometres.

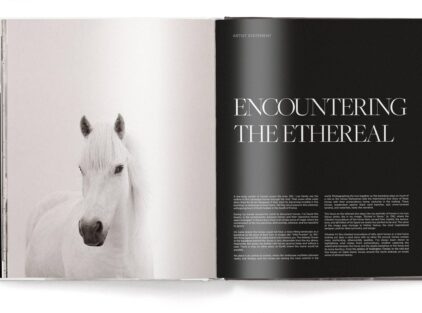

In his book Always a Sailor, he unfolds a journey that is not merely an autobiography, but a kind of “Bridge Log.”

From Oinousses and Psara to the bridges of ships, Vasilis Pateras has lived the intensity of the sea in all its scales – from the gentle swell of an island cove to the great storm of national responsibility.

We speak with him on the occasion of the book, but it quickly becomes clear that the conversation moves beyond its pages. It goes where it always goes: to the weather, the waves, the team, the sense of duty.

—What prompted you to write Always a Sailor?

— I never had the ambition to become a writer. I felt more that I was carrying a story which, if not written down, would slowly be lost, like so many others.

I wanted to leave to anyone who loves the sea a trace of my own journey. Not so that they would remember me, but because I did not want to be just another person who lived and left behind only silence.

—In the opening pages you describe your childhood on fishing boats. Would you like to read or remind us of a short excerpt?

— Let me read you an image from back then:

“I still remember the wooden bunk where we slept exhausted and the thick blanket we covered ourselves with. The ‘Egnousiotis,’ an 18-metre Greek fishing boat belonging to my uncle Giannis, had no comforts, but it did have a permanent smell of fish soup we cooked on the gas stove with spices from the East.”

These images are my childhood. The watch, the holds, the engine room, the shouts of the crew, the stories of the old hands – this was my “school.” I learned early on that the sea does not joke. It respects you only if you respect it. And that sometimes, a child on a bunk can feel more “grown-up” than an adult on land.

—Oinousses and Psara appear in the book almost as characters. What do they mean to you?

— They are my roots. In Oinousses, my father’s birthplace, every house is tied to a ship and every ship’s name flutters on the lips of retired sailors. In Psara, my mother’s homeland, every stone carries a memory of sacrifice. You cannot come from these places and not feel a sense of duty – not only economic or professional, but moral. When I return there, I am not simply going “to the island.” I go to meet all the previous generations who sailed before me; I go to meet those who blessed me.

—In the book you refer to your decision to join the Underwater Demolition Teams (Navy SEALs).

— I remember many people’s surprise when I decided. “With the service you could do, you’re volunteering for the frogmen?” That was the classic question. But for me it was the natural continuation. I had learned to live at sea; I wanted to learn to live it in its harshest, operational form. The Underwater Demolition Teams are a school that never really leaves you.

—What does it mean to go through that training?

— First and foremost, you learn that there is no such word as “easy.” Day and night blur together. You swim for hours, at night, with a weapon in your hand, as part of a team that must remain bound like a fist. You crawl through sand or rocks, carry boats on your shoulders, enter icy waters, dive with minimal visibility. Your body reaches its limit – and then you discover that there is something minimal left inside you… and then again, a little further. The next dive may be deeper, the water colder, the visibility worse, the duration longer.

—What is the most important thing in all this?

— Trust. You learn that your life literally hangs on the man next to you. If he breaks, you are in danger too. This lesson of “together” is the most valuable one. And today, as president of the Frogmen Association, I feel that I continue, in another way, the same chain. We keep alive a body of people who learned to function with absolute trust – to exist in relation to the man next to you, and for him to exist because you exist.

—You were also trained in parachuting. What is the first jump into the void like for a man of the sea?

— Maritime…

—Like a sea breeze?

— When the aircraft door opens, you feel the air like heavy weather on the bridge. Whether you look down at land, or sea, or see nothing at all—the feeling is the same: a thin boundary between control and the unknown. A fine line separating confidence and self-control from chaos. That’s when you understand the value of training, preparation, discipline. If you have them, you jump. If you don’t, those who follow push past you.

—From the UDTs and parachutes, you move to a completely different challenge: first place in the Round Britain powerboat race.

— It was a great dream for a “child of the sea.” In my youth I found myself participating in one of the toughest races in the world, the Round Britain Race, in June 2008, starting and finishing in Portsmouth. Weather, currents, distances – everything is extreme. And yet, there I felt again what I had felt in the UDTs and on fishing boats: that when the team functions, when the boat becomes an extension of your body, you can circle a country – and finish first.

Winning was not just about speed. It was about endurance, persistence, and making the right decisions at the right moment.

—Luck too?

— “Boldness seduces luck,” Gandhi said.

—What will you never forget from that race?

— Everyone remembers the finish. I will never forget the moments when we didn’t know if we would finish at all.

—What do all these have in common with shipping?

— Shipping is continuous risk. No market is ever the same, no voyage is guaranteed. What I learned in the Underwater Demolition Teams—assessing risk, trusting the team, preparing for the worst-case scenario—helped me more than anything. The same goes for racing: knowing when to push the throttle and when to protect your vessel.

At the same time, I never forget my origins. Shipping is not an abstract business activity for me; it is the continuation of my grandfather’s and father’s ships. When I see a vessel berthing in some port of the world, I always think of the small harbour in Oinousses.

—How did the idea of AXION HELLAS come about—turning your inflatable boats into bridges of offering?

— It was a simple thought that matured gradually: since we can go almost anywhere with our boats, why not do it for something more than our own enjoyment? That’s how Axion Hellas was created. A group of people connected to the sea who decided to use it as a road of social contribution.

We go to islands where doctors are not a given, where a child may never have seen a child psychologist or a dentist, where a school has waited years for a small basketball hoop, a village for a playground. Every mission is a small feat – and a great joy.

—Are there images from these missions that have marked you?

— Numerous. A child squeezing a doctor’s hand in relief. A teacher telling us that his students finally felt that someone from the rest of Greece “sees” them. A soldier at a remote outpost welcoming us like relatives and sharing his food with us.

Axion Hellas is a way of telling the people of the border regions: “We haven’t forgotten you.” And that, for me, is worth more than any medal—however deeply I honour the distinctions I have received.

—Speaking of distinctions, you have been honoured by the President of the Republic. How does one experience such an honour?

— Standing before the President of the Republic and hearing that your contribution to the country is being honoured is one of those moments you do not expect. For me, that medal is not a personal ornament. It is recognition of an entire circle of people: my grandparents and parents, whom I hope are proud from above; the people of the sea; the volunteers; the doctors; the frogmen—everyone who contributes quietly to the common good.

—Do you ever wear the medal, or is it on a bookshelf?

— I see it more as an anchor of responsibility than as jewellery. A constant reminder: we are not done; there is still a way to go.

—You were trained to be fearless and unbreakable. Is there anything that frightens you—loss, decay, illness?

— God forbid – only a fool feels no fear. It’s one thing to be aware of danger and manage it, and another to pretend it doesn’t exist.

—What do you fear?

— Anyone who grows up at sea does not fear easily on land. Fear is not always an enemy. It is an alarm that sounds to keep you awake. Recently I fought a battle with my health. All is well.

—Can one be trained not to fear death?

— “Death is an invention of life, to shift onto someone else its failure to be eternal,” as Kiki Dimoula writes.

—What would you say to someone who claims you have an “obsession” with the country’s small border islands?

— I would tell them that if loving your homeland is an obsession, then yes, I am very obsessive. But seriously, I truly believe that if Greece were only its cities and large ports, it would be half a country. The other half is held by small clinics, lonely outposts, single-teacher schools at the edge of the map.

—If you had to sum up the message of Always a Sailor in one sentence?

— That you can change ships, change seas, change roles – but if you lose your compass, you lose everything. My compass was always the sea, the team, and service to my country. If the book manages to make even one young person love this place a little more, test their limits, help where they can, then I feel that the journey of Always a Sailor was worth it.

Illustration by Dimitris Dimarelos