by Apostolos Kotsampasis

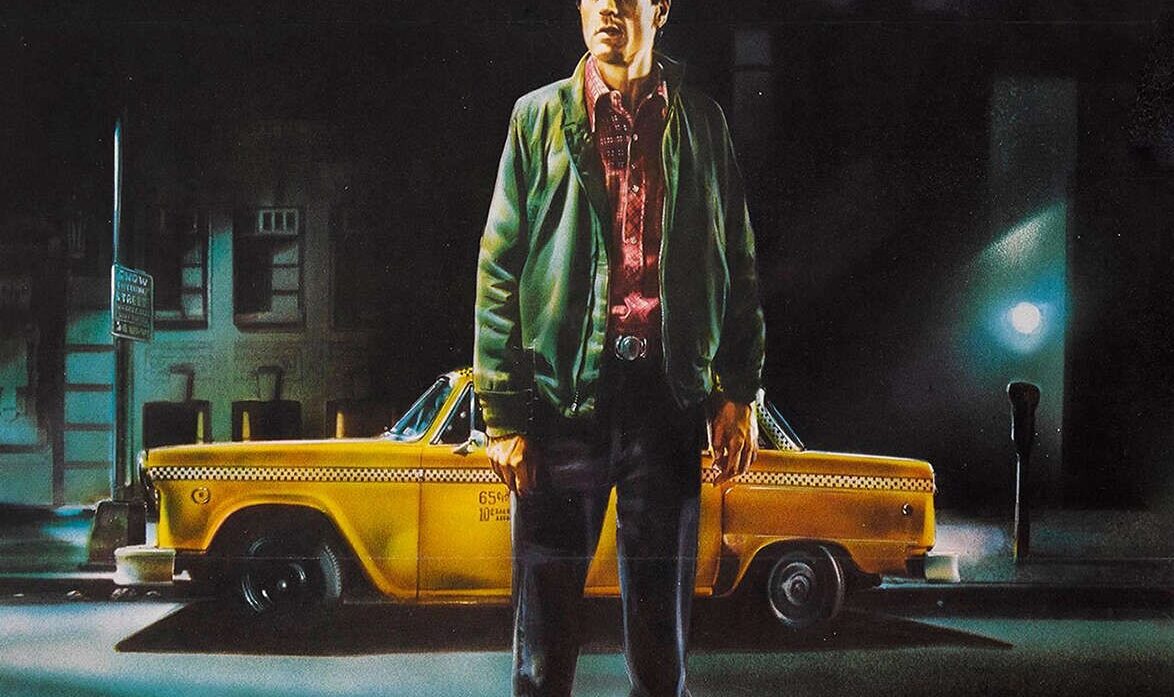

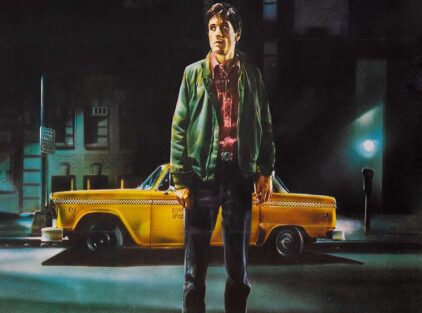

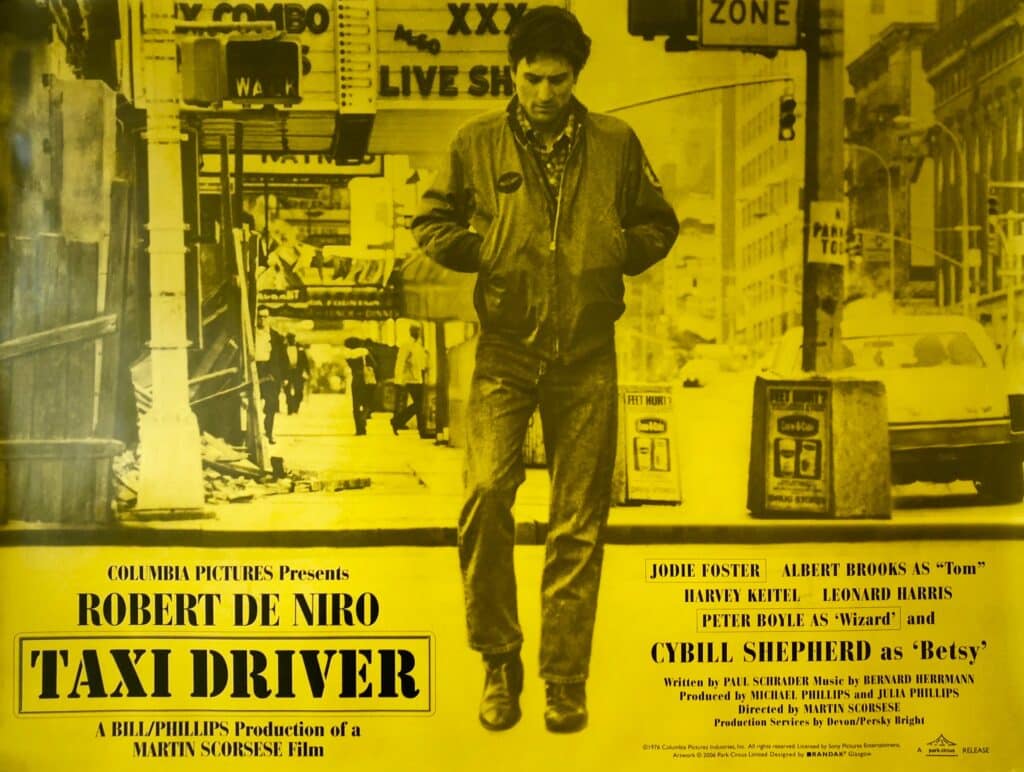

The film Taxi Driver celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2026, and this milestone arrives like a slow replay of an urban decay that never really faded.

Martin Scorsese directed it in 1976, pulling the camera into a New York already decomposing – garbage strikes, near bankruptcy, pimps in Times Square and porn theaters glowing like open wounds. The city wasn’t a backdrop; it was the infection. Steam pipes hissed, trash bags lay torn open, neon lights dripped onto rain-soaked streets. Scorsese shot it with Bernard Herrmann’s final score swelling like a migraine, turning deterioration into opera.

Paul Schrader wrote the script in ten days, two drafts, after his own collapse: a broken marriage, a broken relationship, debts, isolation so absolute he hadn’t spoken to anyone for weeks. Hospitalized with an ulcer, he saw the taxi as a metaphor: an iron coffin traveling through the sewers, the driver surrounded by corpses yet untouched. He reread Sartre’s Nausea, Camus, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man. The inspiration came from the diaries of Arthur Bremer – the would-be assassin of Democratic candidate George Wallace in 1972 – and from Schrader’s own pathology of loneliness, the kind that turns rejection into a weapon. He exorcised it on paper to avoid becoming the character.

Robert De Niro became Travis Bickle, a Vietnam veteran turned psychotic night-shift driver, with a mohawk and the mirror monologue: “You talkin’ to me?” Twelve-year-old Jodie Foster was Iris, the underage prostitute he tries to “save.” Harvey Keitel played Sport, the pimp. Cybill Shepherd was Betsy, the campaign worker he idealizes and then terrifies. Albert Brooks portrayed the manipulative operator. The cast revolves around De Niro’s quiet collapse.

The era was post-Vietnam, post-Watergate – trust in institutions had eroded, paranoia had become normal. Bickle’s fantasy of vigilante justice felt prophetic: Hinckley watched the film obsessively before shooting Reagan in 1981. Fifty years later, the film still hurts – the incels, the lone wolves, the thin line between alienation and monstrosity. Scorsese and Schrader created a mirror, not a movie. We keep looking, and we still recognize the face.