by Hesperia Iliadou de Subplajo*

I was at the Guggenheim for a preview, which turned out to be duller and longer than I expected. It’s still raining and getting dark early, and in Venice you walk everywhere. The aperitivo break somewhere in the middle of the Guggenheim is absolutely necessary. Harry’s Bar or Bauer? Bauer, because the Grand Canal in the rain is lovely! I order Black Rock Chiller. Ordering aperol spritz in Venice is a sin in the best spritz select for those in the know. I order Black Rock Chiller, Fernet Branca because it’s winter and the mint is gone, Tequila because I miss summer and the name Black Rock because “Burning Man” is not forgotten. Davide behind the bar knows me, he doesn’t complain. But why does the word “chiller” always make me think of Chiller? The pronunciation is different, but it’s like… It’s the NTU that haunts me, it’s Athens that I miss too… Chiller it is. I’m trying to think of him in Bauer’s bar. I wonder if he’d ever been to Venice. Everyone passes (Byron, Goethe, Ezra Pound, Hemingway, Stravinsky), but few stay. But Chiller… I can imagine. He’s short, always well-groomed, with an elaborately sculpted, almost architectural period moustache. Yes, definitely architectural, since we’re talking about Ernesto Chiller, the architect of Athens.

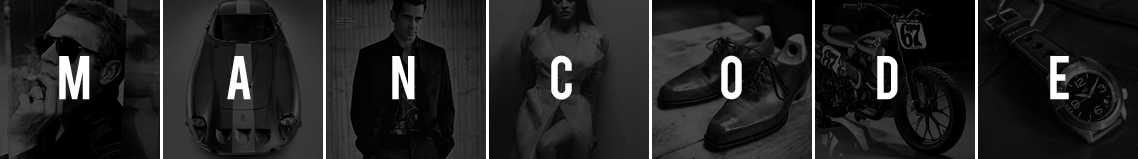

Finds from the excavations of Chiller at the Panathenaic Stadium, lithograph, 1870.

Ernesto Chiller was born in 1837 in a town whose name recalls a tongue twister from a Brothers Grimm fairy tale. The town is called Oberlesnitz and is located in Saxony, far from Greece, which in these years is trying to revive itself after the momentous 1821. Born into a family involved in building in the various expressions it can take, he follows the family tradition and after a first course of study ends up as a designer in the office of Theophilus Hansen. This collaboration with Hansen would inevitably determine the rest of his life, both professional and personal, and in a strange way would also determine the aesthetic form of a city in the making, far away, our own Athens. So if Ernestos had not gone to work for Theophilus, the Athens we know would have been very different, and not only Athens. I think of the town hall in Ermoupolis, Syros: on what steps would someone take a selfie in Ermoupolis today without Chiller. When I was studying at Bartlett’s in London several years ago, I did some research on the imaginary maps and symbol buildings that help us ‘navigate’ the structured sea of the centre in Athens.

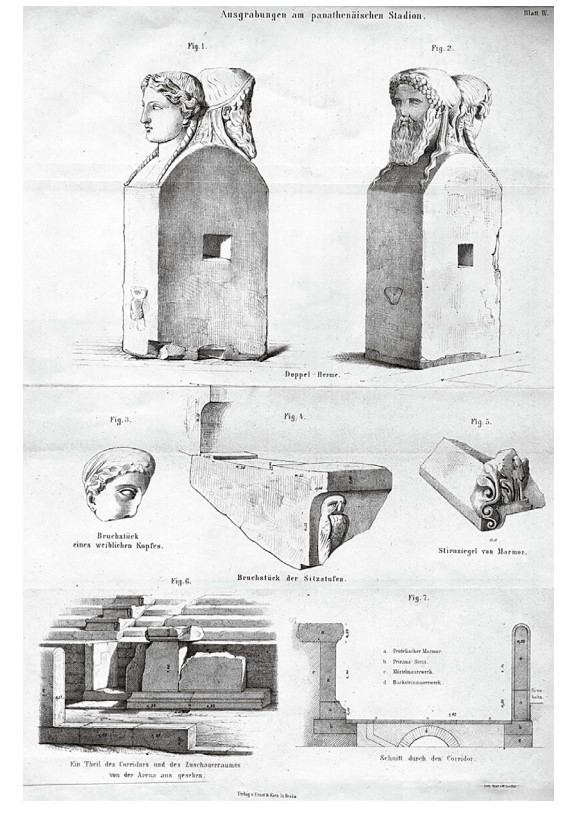

Design of the Panathenaic Stadium with the excavation findings of Chiller, lithograph, 1870.

So I would ask passers-by which buildings were the ones that were key for them on their routes through the city. 85% of the responses made reference to Chiller buildings. So, almost a hundred years after his death in 1923, Athens is still marked in a sophisticated and sensitive, and magically conceivable, way by him. He would arrive in the city for the first time with Theophilus Hansen in 1861, to help supervise the construction of the Athens Academy building, then known as the Sinaia Academy, since it was sponsored by Sina. He would again return to Vienna and, yes, he would also pass through Venice on one of his trips during a second course of study at the Vienna School of Fine Arts, sometime after 1864. So I imagine him among the crowd at St Mark’s. His first stay in Greece had already preceded this, and it was in Vienna in 1876 that this karmic relationship with Greece would be sealed. Here he meets the Greek musician and piano soloist Sophia Doudou, 20 years his junior, whom he marries and with whom he settles in Greece as an independent architectural designer. Here he would occupy the Chair of Architecture at the School of Arts (Polytechnic), be appointed Director of Public Works under Trikoupis, contribute to the tree planting of Lycabettus and take part in excavations. The elements from these studies will all find a place in his architecture and will shape the streets of Athens as we know it.

In a typical photograph we see Ernesto and Theophilus standing together in front of the Academy building during its construction. On the left, with his curiously baggy trousers and tall hat, taller than the others, stands the man who would eventually design and build an unrealistic number of buildings throughout Greece at the time, even by today’s standards (600 perhaps, certainly 500, but in fact it has not yet been possible to make a complete record of all his projects). Looking at other photos of the time, we will see that it is probably a euphemism to call Athens a city at that time. The landscape is completely bucolic, with sheep grazing on the Pillars of Olympian Zeus and shepherdesses spinning wool sitting on broken Doric columns.

The three founders of the Academy, Chiller, Gripenkerle and Hansen, in the large conference room, circa 1880.

In the now classic text by Kostas Biris (“Αι Αθήναι”, 1966, p. 48) we find this reference, written by Konstantinos Bellios, who arrived in Athens in 1836. So this was Athens, and here in this landscape, Chiller would create buildings that are rather like the modern architectural works-towers that spring up in the desert sands of the Emirates. In a parallel to Rem Koolhaas, Nouvelle and Zaha Hadid, Ernest builds everything and has the most select clientele because of his friendship with George I: Palace of the Crown Prince (today’s Presidential Palace), Schliemann Palace (Mint Museum), Royal Theatre, National Archaeological Museum, Stathatos Palace, Syngrou Palace, Royal Mansion in Tatoi, Mega Melas in Aeolou, Municipal Theatre of Athens (no longer exists), St. Luke’s Church, Evelpidon School Administration Building, Old Chemistry, Bageion Hotel in Omonia, Frissiras family building, New Arsakeio, Attikon Cinema. …I can’t remember them all, and that’s just in the center. In Athens I think the saying “just name it and it is his” applies. Chiller can also be found in Piraeus, Patras, Zakynthos, Ermoupolis of course, Pyrgos, Aegio, Tripoli, Milos, Thessaloniki, Gythio, Argos. ‘Chiller’s style was characterized by a precise knowledge and a tasteful rendering of the architectural and decorative elements of the Greek and Renaissance styles in terms of proportions, but also by a cold formality [. …] a calligraphy and orthography of classicist architecture […] through his work, Chiller taught artful and refined building techniques in Athens’, writes K. Biris (‘Athens’, p. 176).

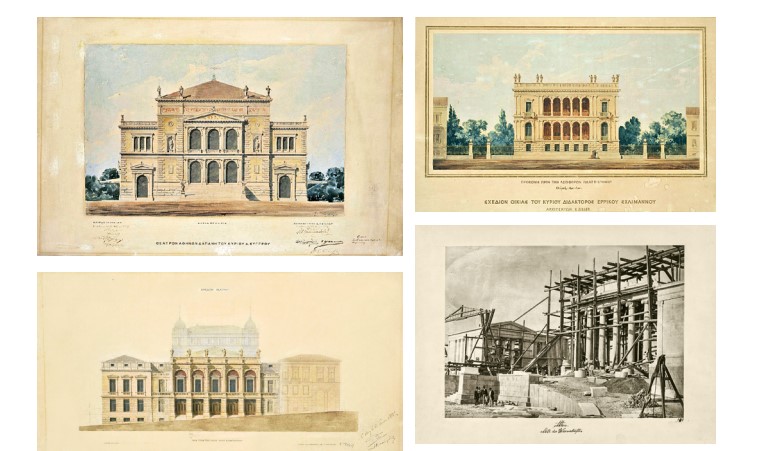

Top left: Municipal Theatre of Athens, main view, 1886 (demolished).

Bottom left: Royal (National) Theatre, main view, 1891.

Top right: Schliemann’s private mansion “Ilion Melathron”, main elevation, 1878.

Right: The construction site of the Academy during the visit of its scholar, Theophilus Hansen, and the painter Gripenkerl from Vienna, circa 1872.

Nevertheless, like any self-respecting great man, he will die broke, but he will leave the city of Athens and us rich from his work. So the next time you pass by a grand neoclassical and not-so-classical building of the era or have a chiller, think of Ernesto: he is still around.

* Hesperia lives and works between Venice and Florence, where she teaches museology and exhibition curation. She started out in Athens and the NTUA, as an architectural engineer with a PhD in urban history, to continue in London with studies in archaeology, art history and museology. She works with NODE Curatorial Research Center in Berlin and Abu Dhabi National Museums association, with architects and museums as a consultant museologist in the design and programming of exhibitions and museum spaces with special character. She has curated Malta’s participation in the 2019 Venice Biennale and is the only woman on UNESCO’s Industrial Heritage Committee. She has a dog and a cat and a house with no white walls.

The photos are from the bilingual book (Greek/German), “Memories of Ernst Chiller” by Marilena Z. Kasimatis which is published by Peak Publishing.